Before we dive into the details of WSGI, why don't we take a bird-eye's view on what happens when a user uses our web application.

Part I: the world through a web server's eyes

Imagine for a moment that you are a web server (e.g. a gunicorn). Your job consists of the following parts:

- You sit around and wait patiently for a request from some kind of a client

- When a client comes to you with a request, you receive this request

- Then, you take this request to a guy called PythonApp and say to him: "Hey dude, wake up! Here is a request from a very important client. Please, do something about it"

- You get a response from this PythonApp guy

- You then take this response back to your client

This is the only thing you do. You just serve your clients. You know nothing about content or anything. That's why you are so good at it. You can even scale up and down processing depending on the demand from the clients. You are so focused on this task.

Part II: PythonApp guy

PythonApp guy is your software (duh!). Whereas a web server should exist and wait for an incoming request all the time, your software exists only at the execution time:

- A web server wakes it up and gives him the request

- It takes the request and executes some commands on it

- It returns a response to the web server

- It goes to sleep

- Web server takes this response back to his client

The only thing it does is execute, not sit around and wait.

The Problem

The scenario above is all good and roses. However, a web server's conversation with the PythonApp guy could have gone a little differently. Instead of:

Hey dude, wake up! Here is a request from a very important client. Please, do something about it

it could have been like this:

Эй, чувак, проснись! Вот запрос от очень важного клиента. Пожалуйста, сделай что нибудь

or it could have been like this:

Ehi amico, svegliati! Ecco una richiesta da un cliente molto importante. Si prega, fare qualcosa al riguardo

or even like this:

嘿,伙计,醒醒吧!这里是一个非常重要的客户端的请求。请做点什么

Do you get it? The web server could have behaved in a number of different ways and the PythonApp guy had to learn all these languages to understand what it is saying and behaving accordingly.

What this means is that, in the past you had to adapt your software to fit the requirements of a web server. Moreover, you had to write different kinds of wrappers in order to make it suitable across different web servers. What developer wants to deal with such things instead of writing code?

WSGI to the rescue

Here is where the WSGI comes in! Understand it as a SET OF RULES for a web server and a web application. The rules for a web server look like this:

Okay, if you want to talk to that PythonApp guy, speak these words and sentences. Also, learn these words as well which he will speak to you. Furthermore, if something goes wrong, here are the curse words that the PythonApp guy will be saying and here is how you should react to them

And the rules for a web application look like this:

Okay, if you want to talk to a web server, learn these words because a web server will be using them when addressing you. Also, you use the following words and be sure that a web server understands them. Furthermore, if something goes wrong, use these curse words and behave in this way

Enough talk, let's fight

Let's take a look at the WSGI application interface to see how it should behave. According to PEP 333, the document which specifies the details of the WSGI, the application interface is implemented as a callable object such as a function, a method, a class or an instance with a __call__ method. This object should accept two positional arguments and return the response body as strings in an iterable.

The two arguments are:

- a dictionary with environment variables

- a callback function that will be used to send HTTP status and HTTP headers to the server

Now that we know the basics why don't we create a web framework which will definitely take away some market share from Django itself :) Our web framework will do something that no one is doing right now: IT WILL PRINT ALL ENVIRONMENT VARIABLES IT RECEIVES. Genius!

(have been watching to much Pewdiepie. Goddammit)

Okay, let's create that callable object which receives to arguments:

def application(environ, start_response):

pass

Easy enough. Now, let's prepare the response body that we want to return to the server:

def application(environ, start_response):

response_body = [

'{key}: {value}'.format(key=key, value=value) for key, value in sorted(environ.items())

]

response_body = '\n'.join(response_body)

Easy as well. Now, let's prepare the status and headers, and then call that callback function:

def application(environ, start_response):

response_body = [

'{key}: {value}'.format(key=key, value=value) for key, value in sorted(environ.items())

]

response_body = '\n'.join(response_body)

status = '200 OK'

response_headers = [

('Content-type', 'text/plain'),

]

start_response(status, response_headers)

And finally, let's return the response body in an iterable:

def application(environ, start_response):

response_body = [

'{key}: {value}'.format(key=key, value=value) for key, value in sorted(environ.items())

]

response_body = '\n'.join(response_body)

status = '200 OK'

response_headers = [

('Content-type', 'text/plain'),

]

start_response(status, response_headers)

return [response_body.encode('utf-8')]

That's it. Our genius web framework is ready. Of course, we need a web server to serve our application and here we will be using Python's bundled WSGI server. But if you want to learn the WSGI server interface, take a look at here.

Now, let's serve our application:

from wsgiref.simple_server import make_server

def application(environ, start_response):

response_body = [

'{key}: {value}'.format(key=key, value=value) for key, value in sorted(environ.items())

]

response_body = '\n'.join(response_body)

status = '200 OK'

response_headers = [

('Content-type', 'text/plain'),

]

start_response(status, response_headers)

return [response_body.encode('utf-8')]

server = make_server('localhost', 8000, app=application)

server.serve_forever()

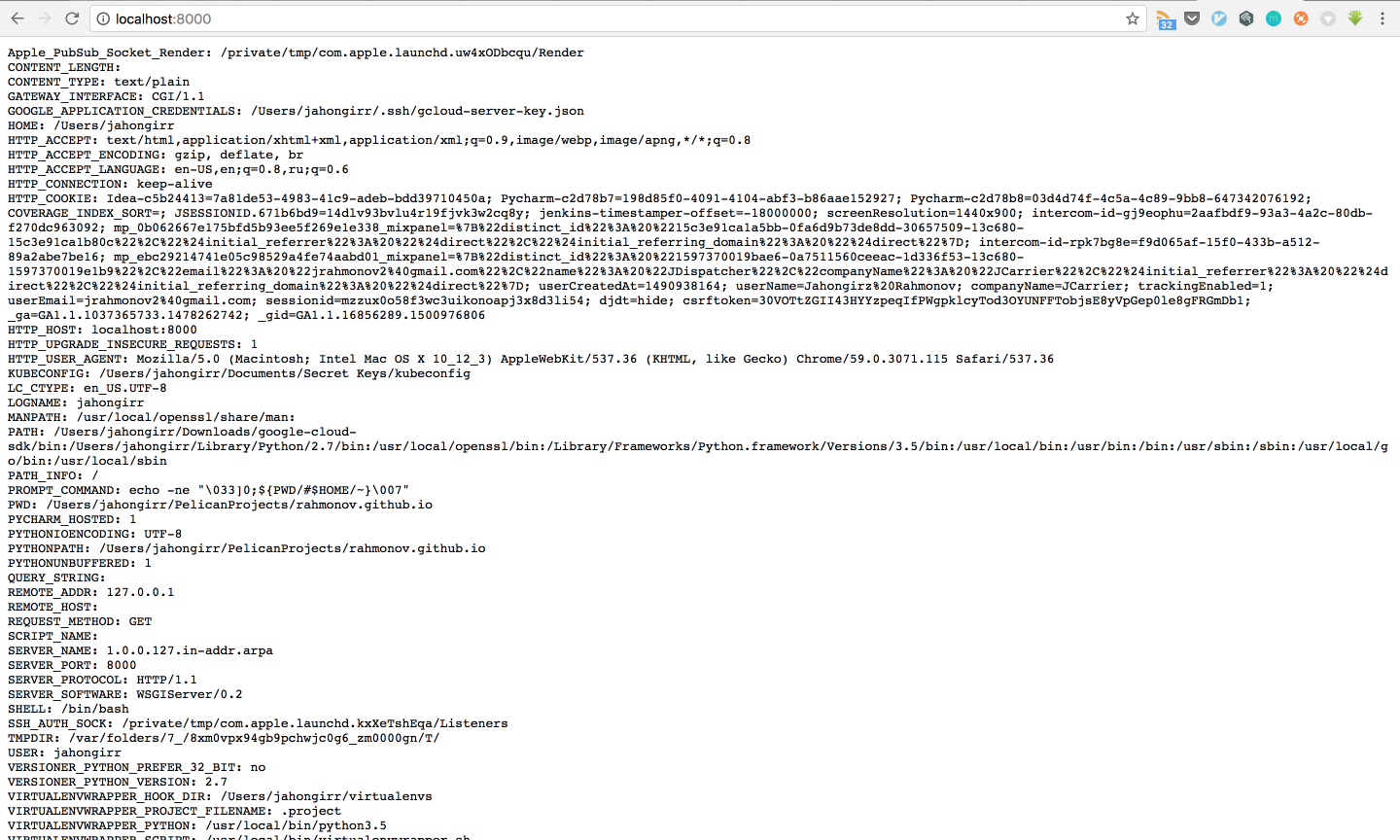

Save this file as wsgi_demo.py and run it python wsgi_demo.py. Then, go to localhost:8000 and you will see all the variables listed:

YES! This framework is going to get very popular!

Now that we know about the WSGI application interface, let's talk about something that we deliberately missed earlier: Middleware.

With middleware, the above scenario will look like this:

- Web server gets a request

- Now, it won't directly talk to the PythonApp guy. It will send it through a postman (middleware)

- The postman delivers the request to the PythonApp guy

- After the PythonApp guy does his job, gives the response to the postman

- The postman delivers the response to the web server

The only thing to note is that while the postman is delivering the request/response, he may tweak it a little bit.

Let's see it in action. We will now write a middleware that reverses the response from our application:

class Reverseware:

def __init__(self, app):

self.wrapped_app = app

def __call__(self, environ, start_response, *args, **kwargs):

return [data[::-1] for data in self.wrapped_app(environ, start_response)]

Simple enough. If we insert this code to the example above, the full code will look like this:

from wsgiref.simple_server import make_server

class Reverseware:

def __init__(self, app):

self.wrapped_app = app

def __call__(self, environ, start_response, *args, **kwargs):

return [data[::-1] for data in self.wrapped_app(environ, start_response)]

def application(environ, start_response):

response_body = [

'{key}: {value}'.format(key=key, value=value) for key, value in sorted(environ.items())

]

response_body = '\n'.join(response_body)

status = '200 OK'

response_headers = [

('Content-type', 'text/plain'),

]

start_response(status, response_headers)

return [response_body.encode('utf-8')]

server = make_server('localhost', 8000, app=Reverseware(application))

server.serve_forever()

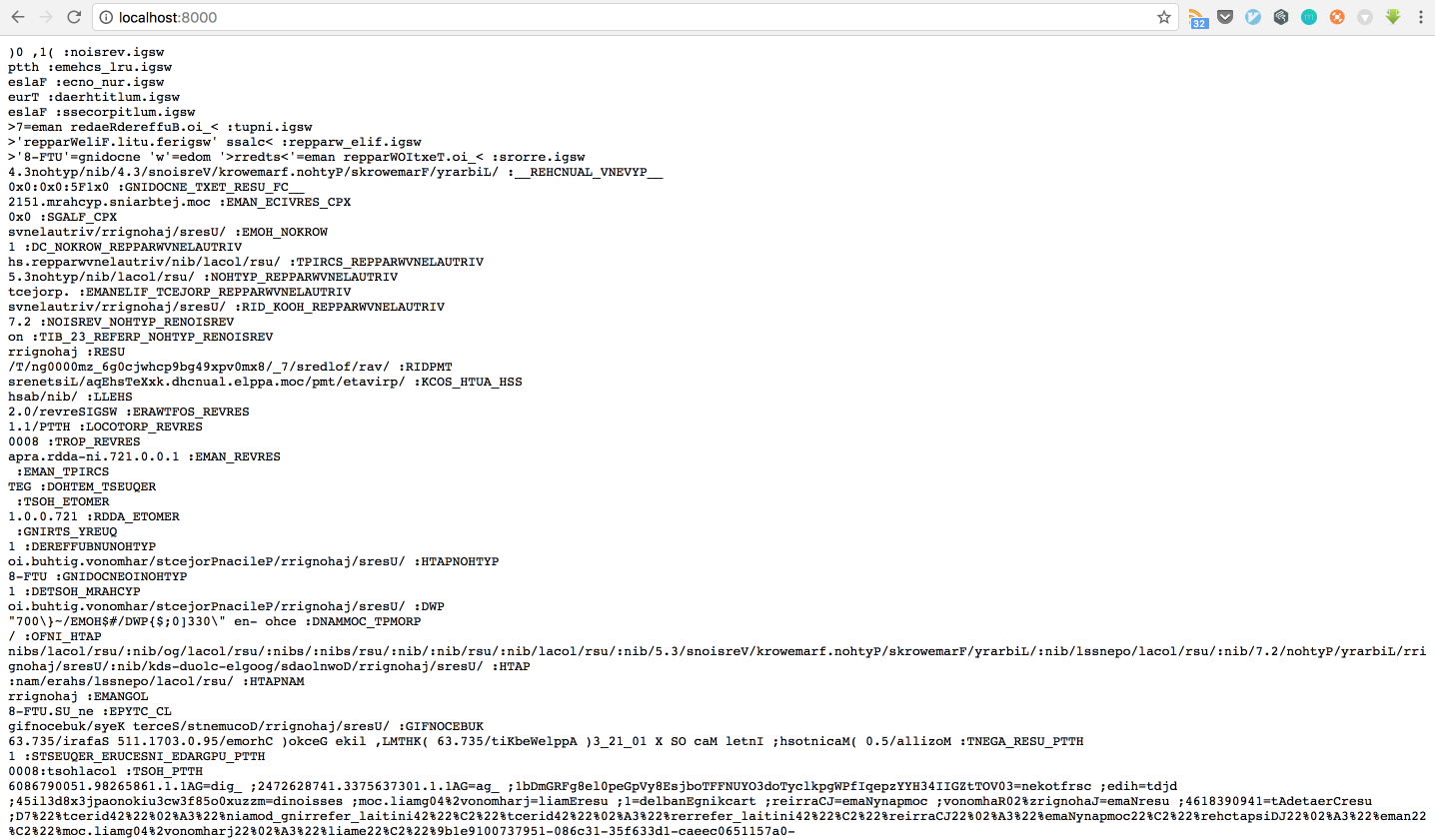

Now, if you run it, you will see something like this:

Beautiful!

Alright, that's it from me today. If you want to learn more about the WSGI, please see the updated PEP 3333. Thanks for reading!

Fight on!